BES2024 BES 2024 CLINICAL CASE REPORTS (10 abstracts)

Are those teeth in your pituitary?

Aurélien Schommers 1 , Iulia Potorac 1 , Gilles Reuter 2 , Cécile Andris 3 , Jean-François Bonneville 4 & Patrick Petrossians 1

1Service d’Endocrinologie, CHU de Liège.2Service de Neurochirurgie, CHU de Liège.3Service d’Ophtalmologie, CHU de Liège.4Service d’Imagerie Médicale, CHU de Liège

Background : Pituitary teratomas are exceptional, with very few cases reported in the literature. Due to their rarity, it is difficult to establish a consensus for their management. We report the case of a young patient who was diagnosed with a non-symptomatic pituitary teratoma containing well-differentiated teeth. No specific treatment was dispensed, but the tumor benefits from a regular follow-up and shows no long-term progression.

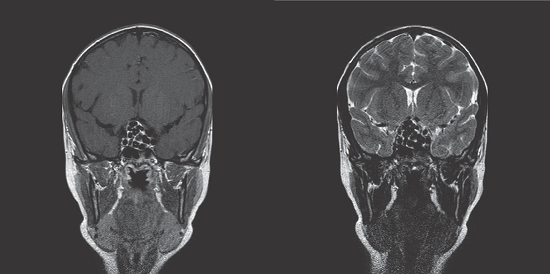

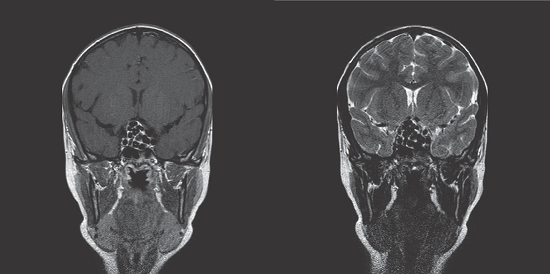

Case presentation: An eleven-year-old boy was referred to pediatrics for a brachiocephalic myoclonus occurring for six months. The patient did not present headaches, visual complaints or signs of intracranial hypertension. The physical examination was unremarkable. MRI of the brain was performed and fortuitously revealed a 27 mm pituitary mass with suprasellar extension and the presence of multiple T1 and T2 hypointense images. The optic chiasm showed signs of compression (Figure 1). The hormonal workup did not reveal any hormonal deficiency. Ophthalmologic examination showed no visual field defect. A germinoma was suspected. Thus, the patient benefited from chemotherapy. A follow-up MRI indicated no sign of tumor response which caused the diagnosis to be reconsidered. A biopsy of the mass was performed, with the removal of four teeth. No epithelial or cellular structure was identified microscopically. The diagnosis of mature teratoma was established. As the patient seemed to show no symptoms related to the teratoma, further surgical removal of the pituitary mass was not performed, and a close follow-up was decided. For the ten following years, subsequent MRIs have shown no sign of tumor progression. Currently, the patient remains asymptomatic.

Discussion: Intracranial teratomas represent 0,5% of all intracranial tumors. They mostly occur during the first two decades of life [1]. They belong to central nervous system germ cell tumors (GCTs), which are classified in three different subclasses: germinomas, non-germinomatous tumors (teratomas, embryonic carcinomas, endodermal sinus tumors, choriocarcinomas), and mixed GCT. The most frequent clinical manifestations include neurological deficits, diabetes insipidus and hypopituitarism [2]. Neuroimaging can help the differential diagnosis, but there is an overlap in the imaging features of GCTs [3]. In fact, non-germinomatous tumors appear heterogenous. Mature teratomas can contain fat, calcifications, cystic and solid components. Histologically, we identify three subtypes of teratomas: mature, immature, and teratomas with a malignant transformation. Mature teratomas are mainly composed of well-differentiated tissue with low mitotic activity, while immature teratomas contain poorly-differentiated fetal tissue. Teratomas with malignant transformation are exceptional and contain malignant somatic tissue [3]. Most of the reported tumors contain tissue issued from the three germ cell layers present in normal organogenesis (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm). However, they may sometimes develop from a single germ cell layer if they show a histologically divergent differentiation [3]. The origin of teratomas is unclear. The most common explanation given is that teratomas originate from totipotent primordial germ cells. They develop from the endoderm in the yolk sac and migrate to the gonadal ridges during weeks 4 and 5 of gestation, but some cells seem to miss their target [4]. Currently, there is no consensus for teratoma management. Surgery is generally recommended [5]. Since any residual portion of a diagnosed mature teratoma may also contain a small part of immature or malignant tissue, recurrence after its partial removal has previously been reported [5]. Surprisingly, in our case, despise the fact that the tumor was not removed, the follow-up has so far shown no sign of progression.

Conclusion: Pituitary teratomas’ management is still debated. Surgery is generally recommended, as all subtypes may include immature or malignant elements. Our case suggests that some of them might show a very low aggressive profile, implying that a simple close follow-up can also be an option. Figure 1.

References: 1. Martha L. Tena Suck, Alma Ortiz Plata, Sergio Moreno Jimenez, Luis A. Tirado García: Pituitary Teratoma: A Case Series of Three Cases. Cureus. 2023 May 8;15(5):e38729. doi:10.7759/cureus.38729. PMID: 37292527; PMCID: PMC10246926.

2. Chiloiro, S., Giampietro, A., Bianchi, A. et al. Clinical management of teratoma, a rare hypothalamic-pituitary neoplasia. Endocrine 53, 636–642 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-015-0814-4.

3. Yang M, Wang J, Zhang L, Liu J. Update on MRI in pediatric intracranial germ cell tumors The clinical and radiological features. Front Pediatr. 2023 May 4;11:1141397. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1141397. PMID: 37215600; PMCID: PMC10192609.

4. Keene DJ, Craigie RJ, Shabani A, Batra G, Hennayake S. Bipartite anterior extraperitoneal teratoma: evidence for the embryological origins of teratomas? Case Rep Med. 2011;2011:208940. doi:10.1155/2011/208940. Epub 2011 Aug 28. PMID: 21949666; PMCID: PMC3163403.

5. Glass T, Cochrane DD, Rassekh SR, Goddard K, Hukin J. Growing teratoma syndrome in intracranial non-germinomatous germ cell tumors (iNGGCTs): a risk for secondary malignant transformation—a report of two cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014 May;30(5):953-7. doi:10.1007/s00381-013-2295-1. PMID: 24122016.

}

}